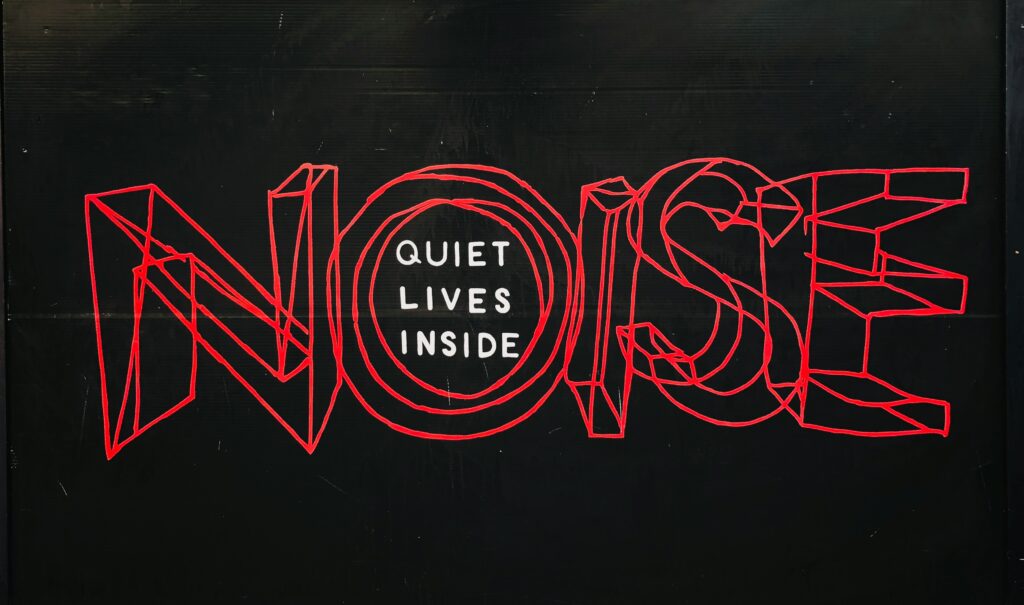

Life is not quiet where I live. Between roadwork, utility crews, and the occasional roofing project nearby, there’s often a steady hum of noise in the background of my home office. Some days it’s manageable. Other days, I can feel the interruptions fracturing my focus before I even sit down to work.

The same thing happens in organizations—though the noise sounds different. The urgent email from a funder. The unexpected staff resignation. The new program idea from a board member. Each is a small disruption, but together they erode your ability to settle into the work that matters.

For nonprofits, distraction has a cost. It slows you down, breaks your flow, and stretches out the work of leadership until what should take a morning bleeds into a week. And on the organizational level, distraction is one of the biggest barriers to turning a strategic plan into reality.

I see this pattern constantly in my work with nonprofit clients. They invest significant time and resources—often six months or more—developing a strategic plan. Boards approve it. Staff celebrate it. Everyone feels energized by the clarity and direction. And then, a few months later, the plan sits on a shelf while everyone wonders why progress feels so slow. It’s not that the plan was flawed, it’s that they underestimated how much space would be needed to implement it.

The Hardest Part of Strategy: Making Space

Writing a strategic plan is hard work, but implementing one is harder. Not because the goals are unrealistic or the vision isn’t inspiring, but because there’s rarely enough space to actually do the work of the plan.

Every organization faces the same fork in the road once the plan is complete:

- Give something up. Stop doing activities that no longer serve the mission, even if they’ve become habits or traditions.

- Find capacity. Create more room for the activities that will move the mission forward.

Most leaders try to do both—keep everything that exists and add everything new. And it’s understandable. Giving something up feels like disappointing a loyal donor, or abandoning a program someone on the board championed, or admitting that what once mattered doesn’t anymore. But when leaders resist making these choices, distraction becomes baked in. The organization is always busy, but rarely moving in a straight line.

Intellectual Capital as a Source of Flow

This is where intellectual capital becomes more than theory—it’s how you reclaim your capacity. If distraction erodes capacity, then strengthening these intangible assets of human, structural, and network capital restores it.

- Human capital: Protecting the energy and focus of staff and volunteers. Too many distractions drain your people faster than you can replenish them. Leaders who model focus, set clear priorities, and make thoughtful trade-offs give their teams permission to do the same. For example, one executive director I know blocks her calendar every Friday morning—no meetings, no emails—so her team sees that protecting focus time is not only acceptable but essential.

- Structural capital: Building systems that support flow instead of breaking it. Meetings without agendas, reports no one reads, or overlapping committees can be as disruptive as a jackhammer outside your window. Strong structures reduce noise, clarify roles, and keep the organization aligned. Try this: For one quarter try a “stop doing” review where teams identify one process to eliminate or simplify. You’ll be surprised how quickly the noise level drops.

- Network capital: Cultivating relationships that amplify rather than scatter. Every partnership or collaboration brings with it both opportunity and demand. The question isn’t only who can we work with? but who helps us stay on course?

When these three forms of intellectual capital are strengthened and aligned, they create organizational flow—the ability to move steadily toward the goals of the plan without constantly being pulled sideways. And they reinforce each other: when human capital is drained, structural capital often breaks down, which then weakens network capital. But the reverse is also true. Strengthen one, and the others often follow.

A Moment for Reflection

The roadwork outside my window will finish eventually. But there will always be something else—a new crisis, a new opportunity, a new demand for attention. The question isn’t how to eliminate distraction, but how to lead in a way that protects the organization’s ability to finish what it started.

So let me ask:

- What’s distracting you—or your organization—from the work of your strategic plan?

- Where might you make a deliberate choice to give something up, or to find capacity, so that the important work has room to breathe?

- Which part of your intellectual capital—human, structural, or network—most needs strengthening to keep your focus steady?

Leaders don’t succeed because their environments are quiet. They succeed because they build the capacity to keep moving forward, even when life is noisy.

October 3, 2025

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Website by Woven Digital Design

| Website by Woven Digital Design

Walker Philanthropic Consulting

Walker Philanthropic Consulting